Introduction

Omphalos was the center stone in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. The term was modified to name the center point of a newborn infant, from which the term umbilical cord emanated. In Latin, umbo denoted the ornamental stud at the center of a shield, from which the term for the umbilicus area was derived. The Anglo-Saxon, nafe, meaning hub of a wheel, was converted to navel.

Uncommon in other animals, abdominal wall hernias are among the most common of all surgical problems. They are a leading cause of work loss and disability and are sometimes lethal. Knowledge of hernias of the abdominal wall (usual and unusual) and protrusions that mimic hernias is an essential component of the armamentarium of the general and pediatric surgeon. Three types of hernia are shown below.

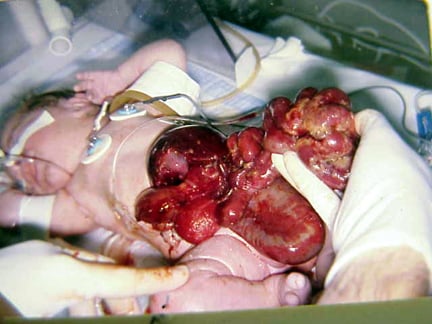

In this baby with gastroschisis, the bowel is uncovered and presents to the right inferior aspect of the cord.

Recent studies

In a study of 780 laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphies (in 569 patients), Coelho et al investigated the types of intraoperative and postoperative complications that can result from the procedure. The authors found that hernias recurred in 14 patients (2.5%) and that intraoperative complications occurred in 28 patients (4.9%), the most common of which was extensive subcutaneous emphysema. Postoperative complications developed in 35 patients (6.2%). Small bowel perforation occurred in 1 patient, and bladder perforation occurred in another. One cohort member developed an extensive, preperitoneal Mycobacterium massiliense infection. No cohort members died. The authors concluded that despite having a low mortality rate, laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy can result in life-threatening complications.1

History of the Procedure

Hippocrates used the Greek hernios for bud or bulge to describe abdominal hernias. Statues of the era portray this condition. The Ebers papyrus, from approximately 1550 BCE, detailed the use of a truss. Celsius used transillumination to differentiate a hernia from a hydrocele and advocated gradual pressure (taxis) in the management of incarcerated hernia (also called irreducible hernia). The earliest recorded surgical efforts were to reduce the hernia through a scrotal incision, to remove the sac and the testis, and to close the area with sutures that spontaneously extruded.

As the church forbade physicians from surgical procedures, nonphysicians (barbers) began developing therapy for surgical problems. De Chauliac advocated escharotics with gradual cicatrization accompanied by prolonged bed rest as the solution for inguinal hernias. Parë followed the operation of Gerald of Metz using a cerclage wire of gold to retard further intestinal protrusion into the scrotum.

In 1700, Littre reported an omphalomesenteric duct trapped in a hernia. Richter described an incarcerated but nonobstructing hernia in 1785. Hunter, in 1756, detailed the embryologic origin of the indirect inguinal hernia. DeGimbernat advocated cutting the ligament that is eponymically associated with him in management of incarcerated femoral hernia. Teale reported the first prevascular femoral hernia in 1846.

Other eponyms associated with inguinal hernias relate to anatomical descriptions by Camper (fascia) (1801), Cooper (ligament) (1804), Cloquet (hernia) (1817), Grynfeltt (hernia) (1866), Hesselbach (triangle) (1814), Laugier (hernia) (1833), Nuck (canal) (1650-1692), Petit (hernia) (1783), and Scarpa (fascia) (1814). Scarpa also previously described a sliding hernia and a spigelian hernia in 1645.

The advent of antisepsis by Lister in 1865 paved the way for a more precise surgical approach to hernia. Finally, physicians could expect success of an operation not being disrupted by infection. In 1871, Marcy felt that closure of the fascia adjacent to the internal ring would provide a reliable repair of the inguinal hernia. Over a decade later, Bassini (1884) formulated an approach to hernia repair that remains the foundation of the modern hernia repair, namely, reconstruction of the floor of the inguinal canal. In the last century, Cheatle used a properitoneal approach in 1920, while McVay (1948) made popular the use of Cooper’s iliopectineal ligament in repair.

Problem

Operative management of hernias, despite being described since antiquity and constituting an essential part of the general surgeon's repertoire of operations, remains controversial. By definition, a hernia is an abnormal protrusion from one anatomical space to another. Variants on the definition of hernia exist with regard to congenital abdominal wall defects. In this article, the author will define these protrusions, their presentations, and their treatment.

An omphalocele is characterized by extension of viscera, often including the liver, from the abdominal cavity into the umbilical stalk, with the contents covered by a translucent, bilaminar sac consisting of fused amnion and peritoneum. (See image below.) On occasion, the sac may tear prenatally or during delivery, making it more difficult to identify. The underlying abdominal wall defect is greater than 4 cm. The umbilical vessels insert onto the sac and traverse serpiginiously to the abdominal wall on the left superior aspect of the sac. On the other hand, gastroschisis is present when midgut viscera protrude through a central abdominal fascial defect and are not covered by a sac. In this case, the extracorporeal viscera are exposed to the amniotic fluid in utero or to the atmosphere postnatally. The responsible fascial defect is usually less than 4 cm and is almost always immediately to the right and inferior to the umbilicus.

Note the translucent sac in this baby with a large omphalocele. Umbilical vessels attach to the sac.

Frequency

As much as 10% of the population develops some type of hernia during life.2 More than a half million hernia operations are performed in the United States each year. Fifty percent are for indirect inguinal hernias, with a male-to-female ratio of 7:1, while 25% are for direct inguinal hernias. Fourteen percent are umbilical (female-to-male ratio, 1.7:1), 5% are femoral (female-to-male ratio, 1.8:1), and 10% are incisional (female-to-male ratio, 2:1). The prevalence of all varieties of hernias increases with age.

Among inguinal hernias, a sliding component is found in 3%; they are overwhelmingly on the left side (left-to-right ratio, 4.5:1). Sliding hernias are much more common in men than in women, and the predominance increases with age. Female infants have a high incidence of sliding tube, ovary, or broad ligament hernias.

Umbilical hernias are much more common in persons of African ethnicity.3 The incidence of umbilical hernias is equal between male and female children, but, in adults, it is 3 times more common in women than in men. Epigastric hernias occur at a prevalence of 0.5% and are more common in males (male-to-female ratio, 3:1).

Spigelian hernias are rare and occur in persons aged approximately 50 years. No sex or side predilection exists for spigelian hernias.

Interparietal, supravesical, lumbar, sciatic, and perineal hernias are rare.

Interparietal hernias are on the right side in 70% of cases, and a similar percentage has testicular maldescent (Denis-Browne pouch).

Reports of internal supravesical hernias are limited, but the literature suggests that they occur more often in men and in elderly people.

Primary perineal hernias occur most often in elderly multiparous women.

Obturator hernias occur most often in thin, elderly women and are more common on the right side.

Richter hernias present late in life, most often in women with femoral hernias.

Littre hernias have a much broader spectrum of hernia site and occur across all ages. The clinical presentation is umbilical, 30%; femoral, 25%; and inguinal, 50%.

In the case of congenital abdominal wall defects, the incidence of omphalocele has only slightly increased over the last few decades to about 1-2.5 in 5000 live births. In contrast, the incidence of gastroschisis has increased markedly over the past 25 years to a current level of 1 in 3600 live births. In addition, the prevalence of gastroschisis has increased by as much as 400% over the last two decades in some areas.

Etiology

The embryology of the groin and of testicular descent largely explains indirect inguinal hernias. An indirect inguinal hernia is a congenital hernia regardless of the patient's age. It occurs because of protrusion of an abdominal viscus into an open processus vaginalis. If the processus contains viscera, it is called an indirect inguinal hernia. If peritoneal fluid fluxes between the space and the peritoneum, it is a communicating hydrocele. If fluid accumulates in the scrotum or spermatic cord without exchange of fluid with the peritoneum, it is a noncommunicating scrotal hydrocele or a hydrocele of the cord. In a girl, fluid accumulation in the processus vaginalis results in a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck.

The inguinal canal forms by mesenchyme condensation around the gubernaculum, which is Latin for rudder because it guides the testis into the scrotum. During the first trimester, the gubernaculum extends from the testis to the labioscrotal fold. The processus vaginalis and its fascial coverings also form during the first trimester. A bilateral oblique defect in the abdominal wall develops during the sixth or seventh week of gestation as the muscular wall develops around the gubernaculum. The processus vaginalis protrudes from the peritoneal cavity and lies anteriorly, laterally, and medially to the gubernaculum by the eighth week of gestation.

The testis produces many male hormones beginning at the eighth week of gestation. At the beginning of the seventh month, the gubernaculum begins a marked swelling influenced by a nonandrogenic hormone, probably a mullerian inhibiting substance. This results in expansion of the inguinal canal and the labioscrotal fold, forming the scrotum. The genitofemoral nerve also influences migration of the testis and gubernaculum into the scrotum under androgenic control. The female inguinal canal and processus is much less developed than the male equivalent. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum is converted to the round ligament. The craniad part of the female gubernaculum becomes the ovarian ligament.

Gonads develop on the medial aspect of the mesonephros during the fifth week of gestation. The kidney then moves cephalad, leaving the gonad to reside in the pelvis until the seventh month of gestation. During this time, it retains a ligamentous attachment to the proximal gubernaculum.

The gonads then migrate along the processus vaginalis, with the ovary descending into the pelvis and the testis being enwrapped within the distal processus, known as the tunica vaginalis. The processus fails to close adequately at birth in 40-50% of boys. Therefore, other factors play a role in the development of a clinical indirect hernia. A familial tendency exists, with 11.5% of patients having a family history. The relative risk of inguinal hernia is 5.8 for brothers of male cases, 4.3 for brothers of female cases, 3.7 for sisters of male cases, and 17.8 for sisters of female cases.

Pathophysiology

Inguinal hernias

The pinchcock action of the musculature of the internal ring during abdominal muscular straining prohibits protrusion of the intestine into a patent processus. Paralysis or injury to the muscle can disable the shutter effect. In addition, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis flattens during tensing, thus reinforcing the inguinal floor. A congenitally high position of the aponeurotic arch might preclude the buttressing effect. Neurapraxic or neurolytic sequelae of appendectomy or femoral vascular procedures may contribute to a greater incidence of hernia in these patients.

Repetitive stress as a factor in hernia development is suggested by clinical presentations. Increased intra-abdominal pressure is seen in a variety of disease states and seems to contribute to hernia formation in these populations. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure is associated with chronic cough, ascites, increased peritoneal fluid from biliary atresia, peritoneal dialysis or ventriculoperitoneal shunts, intraperitoneal masses or organomegaly, and obstipation. (See images below.) Other conditions with increased incidence of inguinal hernias are extrophy of bladder, neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage, myelomeningocele, and undescended testes. A high incidence (16-25%) of inguinal hernias occurs in premature infants; this incidence is inversely related to weight.

A 6-month-old boy with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling.

A 6-month-old boy with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling (same patient as in above image). Abdominal radiograph shows incarcerated shunt within a communicating hydrocele. Repair of the hydrocele relieved the increased intracranial pressure.

The rectus sheath adjacent to groin hernias is thinner than normal. The rate of fibroblast proliferation is less than normal, while the rate of collagenolysis appears increased. Sailors who developed scurvy had an increased incidence of hernia. Aberrant collagen states, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, fetal hydantoin syndrome, Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, Hunter-Hurler syndrome, Kniest syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Morquio syndrome, have increased rates of hernia formation, as do osteogenesis imperfecta, pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy, and Scheie syndrome. Acquired elastase deficiency also can lead to increased hernia formation. In 1981, Cannon and Read found that increased serum elastase and decreased alpha1-antitrypsin levels in people who smoke contribute to an increase in the rate of hernia in those who smoke heavily. The contribution of biochemical or metabolic factors in the creation of inguinal hernia remains speculative.

Umbilical hernias

Umbilical hernias in children are secondary to failure of closure of the umbilical ring, but only 1 in 10 adults with umbilical hernias reports a history of this defect as a child. The adult umbilical hernia occurs through a canal bordered anteriorly by the linea alba, posteriorly by the umbilical fascia, and laterally by the rectus sheath. Proof that umbilical hernias persist from childhood to present as problems in adults is only hinted at by an increased incidence among black Americans. Multiparity, increased abdominal pressure, and a single midline decussation are associated with umbilical hernias.

Congenital hypothyroidism, fetal hydantoin syndrome, Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and disorders of collagen and polysaccharide metabolism (such as Hunter-Hurler syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), should be considered as possibilities in children with large umbilical hernias.

Congenital abdominal wall defects

The underlying embryogenic factor in omphalocele and gastroschisis is deficient closure of the developing anterior wall at the umbilical stalk. Variations in lateral fold migration can result in omphalocele and gastroschisis.4 In addition, most children with omphalocele and all children with gastroschisis have intestinal malrotation, as their extracoelomic location precludes normal attachment of the intestines to the posterior peritoneum.

Improper development of other portions of the abdominal wall leads to specific anomalies. In 1967, Duhamel proposed that maldevelopment of the superior (cephalad) of the 4 folds producing the abdominal wall leads to the thoracic, sternal and diaphragmatic, and abdominal wall defects that make up the upper midline syndrome or pentalogy of Cantrell. In this syndrome, there is a bifid sternal cleft, anterior diaphragmatic defect, anterior pericardial defect, epigastric omphalocele, and congenital cardiac defects. Maldevelopment of the inferior (caudal) fold produces pelvic, hindgut, sacral, genital, and bladder defects. Lower midline syndrome includes a hypogastric omphalocele, extrophy of the bladder or cloaca, vesicointestinal fissure, colonic atresia, imperforate anus, sacral vertebral defects, and often meningoceles.

Lateral fold maldevelopment results in omphalocele and gastroschisis. It has been postulated that an omphalocele results from persistence of the umbilical stalk in the somatopleure. Approximately 20% of infants with omphaloceles have an associated chromosomal abnormality, such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18, trisomy 21, or Klinefelter syndrome. An omphalocele-exstrophy-imperforate anus-spinal defects (OEIS) complex is characterized by a combination of omphalocele, exstrophy of the bladder, an imperforate anus, and spinal defects.5

Over 50% of infants with omphaloceles have associated neurologic, urinary tract, cardiac, and skeletal anomalies. The liver is present in the omphalocele sac in 35% of patients. In small omphaloceles, there is a high coincidence of Meckel diverticulum. Maternal smoking is associated with an increased prevalence of omphalocele and gastroschisis. An increased incidence of abdominal wall defects is related to surface water atrazine and nitrate levels.6

Gastroschisis is thought to be the result of a failure of the umbilical coelom to develop to an appropriate size. The intestine then ruptures out of the body wall to the right of the umbilicus, where a slight weakness exists secondary to resorption of the right umbilical vein early in gestation. Gastroschisis is associated with intestinal atresias in 10-15% of cases, likely due to an interruption of the vascular supply to the intestine. Experimentally, administration of the insecticide methylparathion has produced gastroschisis. Transplacental transmission of such teratogens helps explain gastroschisis in siblings with different fathers.

Other hernias

Aberrant formation of the decussations of the linea alba, leading to a midline pattern of single anterior and posterior lines, predisposes to the formation of epigastric hernias (epiploceles). Abnormal orientation of the semilunar and semicircular lines, in combination with obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure, aging, and rapid weight loss, leads to the production of spigelian hernias.

Internal supravesical hernias probably arise from congenital deficiency in the fasciae. The perihernial fasciae or musculature may be malformed in lumbar, femoral,7 and other abdominal hernias. Interparietal hernias are often a product of ectopic testicular descent. Multiparity and age produce laxity of the pelvic floor to cause obturator hernias and perineal hernias.

Presentation

History and physical examination remain the best means of diagnosing hernias. The review of systems should carefully seek out associated conditions, such as ascites, constipation, obstructive uropathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cough.

Inguinal hernia

The diagnosis of hernia is usually made because a patient, parent, or provider sees a bulge in the inguinal region or scrotum. This bulge may be intermittent as the herniating viscus may or may not enter the space depending on intra-abdominal pressure. In infants, the only symptom of a hernia may be increased irritability, especially with a large hernia. Hernias in older children and adults may be accompanied by a dull ache or burning pain, which often worsens with exercise or straining (eg, coughing). Neuralgia of the ilioinguinal nerve may present with a sudden stabbing pain in the distribution. (See images below.)

Erythematous edematous left scrotum in a 2-month-old boy with a history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Local signs of this magnitude preclude reduction attempts.

The testis at operation in a 2-month-old boy with a history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours (same patient as in above image). A capsulotomy was performed, but atrophy occurred. He also required a bowel resection.

Examination of an adult is best performed from the seated position with the patient standing. One visualizes the inguinal canal areas for the bulge. Frequently, a provocative cough is necessary to expose the hernia. The cough is repeated as the examiner invaginates the scrotum and feels for an impulse. The diameter of the internal ring is assessed. Palpation of the cord structures is performed with the finger gently rolling perpendicular to the long axis of the cord just medial to the internal ring and can detect thickening of the cord.

In children, invagination of the scrotum is counterproductive as a hyperactive cremasteric muscle contraction reduces hernial contents into the peritoneum. Palpation of the cord in the subtle hernia of a child allows recognition of a thickened cord, particularly during straining, which can be easily prompted by tickling the child. There may be the sensation of rubbing two layers of silk together (the so-called silk sign). If the hernia is not demonstrable in the supine position, examine the child in the upright position while applying intermittent manual pressure to the abdomen. If one looks down at an angle from the infant's chest level toward the groin, a combination of gravity and increased intra-abdominal pressure inflates the open sac to confirm the hernia or hydrocele. Of note, the inguinal rings may be of normal size even in children with very large hernias.

In a sliding inguinal hernia, a portion of viscus or its mesentery constitutes part of the hernia sac. The bladder can be seen medially in the hernia sac, while portions of the colon (cecum on the right side, sigmoid on the left side) may be part of any hernia sac. In females, the ovary or fallopian tubes may become part of the wall of the hernia sac and must be carefully preserved during repair.

If the visceral contents of a hernial sac do not easily reduce into the peritoneal cavity, the hernia is incarcerated. If the contents cannot be reduced at all, the hernia is irreducible. In chronic hernias, adhesions may impair reduction. Up to 15% of children, especially young infants, present with incarceration. Four out of five children do not need an immediate operation as attempts at reduction are often successful. An emergency hernia operation has 20 times the risk of complications versus an elective repair; therefore, reduction of an incarcerated hernia should be attempted by an appropriately experienced practitioner and conscious sedation should be used if necessary. A solid, almondlike feeling mass within the labia majora of a girl is usually an ovary, which is the most frequently incarcerated intra-abdominal organ in female infants.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele usually transilluminates on examination. However, gas-filled intestines also transilluminate, thus precluding diagnostic aspiration. If the scrotal size vacillates or one can squeeze fluid from the sac into the peritoneum, a communicating hydrocele is present. Communicating hydroceles without an obvious hernia component should be repaired electively. Hydroceles are insignificant if they are present at birth, bilateral, soft, and peritesticular; do not persist beyond 6 months; and do not fluctuate in size. Since most physiologic noncommunicating hydroceles resolve spontaneously, an operation is generally confined to those older than 1 year, those that develop communication, or those that appear painful to the child.

An acute hydrocele may present in childhood as a rapidly growing, painful scrotal swelling simulating an incarcerated hernia. Palpation of the cord structures at the internal ring while assessing their mobility helps distinguish between these 2 entities. A hydrocele is more mobile, has a defined proximal margin, and is not thick. A hydrocele of the cord presents in the inguinal canal as a nontender, rubbery, round mass.

An abdominoscrotal hydrocele extends from the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. With an infant, a digital rectal examination with careful internal examination of the ring can differentiate an incarcerated hernia from a hydrocele. The child should have an operation for clarification if the situation is equivocal or if the intra-abdominal component is causing mass effect on other organs or obstructive symptoms.

Other hernias

Hernias are the leading cause of intestinal obstruction in the world. Hidden hernias, such as obturator, femoral, or lumbar hernias, should be considered as causes of bowel obstruction. Intense pain is suggestive of strangulation with ischemic bowel. Torsion of the bowel on entry into the sac may lead to precipitous symptoms, while a more gradual onset of pain arises from progressive lymphatic, venous, and then finally arterial compromise secondary to occlusion at the neck of the sac.

Spigelian hernias present with local pain and signs of obstruction from incarceration. This pain increases with contraction of the abdominal musculature. Interparietal hernias between the layers of the abdominal wall present in a similar manner. A mass may be just superior and lateral to the external ring, and the scrotum may not contain a testis. Internal supravesical hernias may have obstructive symptoms of the intestinal tract or those resembling a urinary tract infection. Vague flank discomfort combined with an enlarging mass in the flank suggests a diagnosis of lumbar hernia.

A testicular tumor is usually presumed when splenogonadal fusion presents as a scrotal mass. Splenic tissue recognized on frozen section negates the need for orchiectomy. A 2- to 4-mm mass of yellow-tan tissue found in 1 out of 40 hernia repairs is an ectopic adrenal rest. The proximity of the developing testis and the adrenal gland invites adherence of the two with the adrenal fragment accompanying the testis into the ectopic position.

The differential diagnoses of a groin mass inferior to the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral vessels include an incarcerated femoral hernia, lymphadenopathy secondary to a variety of inflammatory or neoplastic processes, and soft tissue tumors. Peritoneal signs and intestinal obstruction are suggestive of an incarcerated femoral hernia. With common lymph node swelling, the mass is located superficial and inferior to the femoral ring. On examination, enlarged lymph nodes feel firm, somewhat lobulated, and fairly mobile. A primary lesion, such as a cut, scratch, or open wound, should be sought by careful examination of the lymph node drainage area. Culture of the lymph node aspirate guides antibiotic therapy.

Children commonly develop cat-scratch disease lymphadenitis. Feline contact by a scratch or bite causes Bartonella henselae infection. A papule develops in 3-5 days, followed by regional lymphadenopathy in 1-2 weeks. Attendant symptoms of fever, malaise, myalgia, and anorexia; encephalitis; oculoglandular disease; and severe systemic disease complicate 12% of cases. By 2 months, symptoms usually resolve spontaneously. Infections, such as toxoplasmosis, tularemia, infectious mononucleosis, Actinomyces israelii, and HIV, can also cause inguinofemoral adenopathy. In addition, some athletic individuals may have painful reactive inguinal or femoral lymph nodes from repeated trauma.

Prevascular femoral hernia is rare and manifests as a bulge. It may be mistaken for a femoral aneurysm. External femoral hernias pass beneath the inguinal ligament to lie lateral to the femoral vessels and deep to the iliopubic tract. The hernia of Laugier traverses a defect in the lacunar ligament. A hernia of Cloquet results from an abnormal insertion of the pectineus muscle, which allows perforation of the aponeurosis as the hernia sac courses over the femoral canal. The retrovascular hernia sac descends in the posterior sheath of the femoral vein.

Obturator hernias have intermittent, acute, and severe hyperesthesia or pain in the medial thigh or in the region of the greater trochanter. The symptoms are usually relieved by flexion of the thigh and are worsened by medial rotation, adduction, or extension at the hip. Rarely, there is a palpable mass in the medial upper thigh. A tender mass in the gluteal area that is increasing in size is suggestive of a sciatic hernia. Sciatic neuropathy and symptoms of intestinal or ureteral obstruction can also occur. Perineal hernias generally present as a perineal mass with discomfort on sitting and occasionally have obstructive symptoms with incarceration.

An umbilical hernia presents as a central, midabdominal bulge. Altered sensorium and obesity enhance the danger of incarceration. Hypertrophic, hyperpigmented, papyraceous skin is testimony to high pressure on the skin. The size of the fascial defect and whether it is circular provide management clues.

Diastasis recti or a widened linea alba has no clinical significance and does not require operative repair. However, there may be small openings in the linea alba through which preperitoneal fat can protrude. These epigastric hernias occur in children as well as in adults, suggesting that the defects are congenital. The name paraumbilical hernia applies when this defect is adjacent to the umbilicus, while the term epiplocele or ventral hernia is used to describe more craniad defects. These midline hernias present as lumps anywhere along the linea alba and tend to cause sudden severe pain with exercise.

Some neonates have delayed separation of the umbilical cord remnant associated with secondary bacterial colonization and low-grade infection. The salmon pink, cobblestone appearing friable mass that later persists at the umbilicus is termed an umbilical granuloma. A polyp with a glistening, cherry-red smooth surface is usually an umbilical polyp with intestinal or bladder mucosa present (such as an omphalomesenteric duct or urachal remnant).

Congenital abdominal wall defects

Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening can help identify ventral wall defects in the fetus during the second trimester. Prenatal ultrasonography can define the location of the abdominal wall defect, the status of the viscera, its involvement with associated structures, and the presence of additional malformations. Recognition of a small omphalocele or hernia of the umbilical cord stalk may not occur until after delivery. This may result in compromise of the small bowel or damage to an omphalomesenteric duct as the cord is clamped. Therefore, the cord should be clamped well away from the abdomen in an infant with an unusual cord base or widened umbilical cord base to prevent iatrogenic injury to the intestine.

Indications

Inguinal hernias

In general, the presence of an inguinal hernia in the absence of mitigating factors dictates repair to prevent the complications of prolonged exposure, such as incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation.8 Although pressure reduction of an incarcerated hernia is generally safe, failure to reduce is not infrequent and mandates prompt exploration. Signs of inflammation or obstruction should obviate attempts at reduction. Difficult reduction should promptly be followed by repair. Unintentional reduction of the intestine with vascular compromise leads to perforation and peritonitis with high morbidity and mortality rates. En masse reduction following vigorous attempts at reducing a hernia with a small fibrous neck results in ongoing compromise of the entrapped bowel.

Umbilical hernias

Umbilical hernia repair in the adult is indicated for incarceration, a small neck in relation to the size of the hernia, ascites, chromatic skin change, or rupture. The approach to management of an umbilical hernia in a child relates to the natural history of umbilical hernias and their importance in adulthood. Most umbilical hernias close spontaneously in children during the preschool-aged period. Therefore, repair of an umbilical hernia is not indicated in children younger than 5 years unless the child has a large proboscoid hernia with thin, hyperpigmented skin or is undergoing an operation for other reasons or if the hernia causes familial or social problems. The size of the fascial defect rather than the size of the external protrusion predicts potential for spontaneous closure. Walker demonstrated that fascial rings measuring less than 1 cm in diameter usually close, while rings larger than 2 cm seldom close spontaneously. Therefore, many pediatric surgeons will repair umbilical hernias with large fascial defects (>2.5 cm) earlier than the smaller counterparts.

Incarceration of umbilical hernias is rare in the pediatric population. The Johns Hopkins Hospital reported only 7 children in a 15-year period with an incarcerated umbilical hernia. Interestingly, 101 cases of umbilical hernia incarceration occurred in adults at that institution during the same 15-year period. Omentum is the most frequently incarcerated organ.

Other hernias

Painful preperitoneal fat in an epiplocele or paraumbilical hernia may be incarcerated. As these defects will not close spontaneously and a propensity exists for painful strangulation, elective outpatient repair is recommended. Because of the potential for incarceration, spigelian hernias should be repaired, as should interparietal hernias, supravesical hernias, and lumbar, obturator, sciatic, and perineal hernias. Of note, strangulation can occur in a Richter hernia without evidence of incarceration or obstruction.

Relevant Anatomy

Anterior abdominal wall

The anterior abdominal wall is composed of multilaminar mirror image muscles, the associated aponeuroses, fasciae, fat, and skin. Laterally, 3 muscle layers with fascicles run obliquely in relation to each other. Each inserts into a flat white tendon, known as an aponeurosis.

The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate on the pubis inferiorly and insert on the ribs superiorly. The muscle has 4 transversely oriented tendinous bands variably spaced. At the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscles is the linea semilunaris where the aponeurosis serves as an insertion for the lateral musculature. The lower edge of the posterior sheath midway between the umbilicus and the pubis with its concavity oriented toward the pubis defines the semicircular line.

Above this line, anterior and posterior laminae form from division of the internal oblique aponeurosis. The posterior lamina joins the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and forms the posterior rectus sheath. The anterior rectus sheath results from fusion of the anterior lamina and the external oblique aponeurosis. The external oblique aponeurosis forms the external lamina of the anterior sheath below the semicircular line. Fusion of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis aponeuroses forms the internal lamina of the anterior sheath. The posterior surface of the rectus muscles is covered with transversalis fascia below the semicircular line. The midline linea alba represents a decussation of these fibers from the different aponeurotic layers.

The external oblique muscle originates on the lower 8 ribs with obliquely and inferiorly directed fascicles inserting into its aponeurosis. Deep to the external oblique muscle is the internal oblique muscle with obliquely and superiorly oriented fascicles arising from the iliac fascia deep to the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, and from the lumbodorsal fascia. It inserts into its aponeurosis, the rectus sheath, and into the lower ribs and cartilages superiorly.

The transversus abdominis muscle is most internal of the lateral abdominal wall musculature. The fascicles are generally transversely oriented. It arises from the lateral iliopubic tract, from the iliac crest, the lumbodorsal fascia, and the caudad 6 ribs. It inserts principally into its aponeurosis and fuses with the internal oblique aponeurosis to become the posterior rectus sheath. The caudad margin curves to form the transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch as the upper edge of the internal ring and above the medial floor of the inguinal canal. In 3% of cases, this arch may combine with the internal oblique aponeurosis to form the conjoined tendon.

The innominate fascia overlies the external oblique muscle. The transversalis fascia forms an investing fascial envelope of the abdominal cavity. A variable layer of preperitoneal fat separates the peritoneum from the transversalis fascia.

Posterolateral (lumbar) region

The quadratus muscle originates from the iliac crest and the iliolumbar ligament lumborum from between iliac crest and the fifth lumbar transverse process. It then inserts along the 12th rib. The psoas muscle arises from vertebrae T-12 through L-5 and passes downward under the inguinal ligament to insert on the lesser trochanter.

The serratus posterior inferior muscle originates from the lumbodorsal fascia and inserts along the 4 lowest ribs. The sacrospinalis muscle runs along the spinous processes for the entire length of the spine.

The latissimus dorsi muscle originates on the posterior third of the iliac crest, the spinous processes of the sacral and lumbar vertebrae, and the lumbodorsal fascia. From this wide origin, the muscle inserts as a tendon into the intertubercular groove of the humerus.

The superior lumbar triangle of Grynfeltt-Lesshaft is bounded superiorly by the 12th rib, the posterior lumbocostal ligament, and the serratus posterior inferior muscle; inferiorly by the superior border of the internal oblique muscle; and posteriorly by the lateral border of the sacrospinalis muscle. The deep margin of the superior lumbar triangle is the transversus abdominis muscle, and the superficial margin is the latissimus dorsi muscle. Spontaneous lumbar hernias occur more commonly because the potential space is larger and more constant than the inferior lumbar triangle.

The inferior lumbar triangle of Petit has posterior bounds of the latissimus dorsi muscle, anterior bounds of the external oblique muscle, and inferior bounds of the iliac crest.

Inguinal region

Vessels regularly found during inguinal hernia repairs are the superficial circumflex iliac, superficial epigastric, and external pudendal arteries that arise from the proximal femoral artery and course superiorly. The inferior epigastric artery and vein run medially and craniad in the preperitoneal fat near the caudad margin of the internal inguinal ring.

The external iliac vessels pass posterior to the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract and anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath. The external spermatic artery arises from the inferior epigastric artery just caudad to the internal inguinal ring to supply the cremaster muscle.

The inguinal ligament bridges the space between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine to rotate posteriorly and then superiorly to form a shelving edge. It is the caudad edge of the external oblique aponeurosis. The ligament revolves medially to create the lacunar ligament. The lacunar ligament inserts on the pubis and courses medially and superiorly toward the midline. The external oblique aponeurosis has a triangular opening with a superior apex through which the cord enters the inguinal canal.

The transversus abdominis muscle predominates as a layer of the abdominal wall for the prevention of inguinal hernias. The transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch inserts inferiorly on the Cooper ligament and contributes to the anterior rectus sheath medially.

The pectineal ligament courses from the superior part of the superior pubic ramus periosteum. The components incorporate fibers from the lacunar ligament, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, and the pectineus muscle.

An aponeurotic band from the caudad portion of the transversus abdominis muscle creates the iliopubic tract. It is the anterior margin of the femoral sheath and the caudad border of the internal ring. The course is from the superior pubic ramus medially to the iliopectineal arch and iliopsoas fascia, anterior to the femoral vessels, and then laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine.

The iliacus fascia thickens as it exits the pelvis to form the iliopectineal arch. The fascia curves forward, lateral to the external iliac vessels, and combines with fibers from the inguinal ligament, the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and from part of the ligament lateral attachment of the iliopubic tract. The external iliac vessels pass beneath the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract but anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath.

The femoral sheath, with contributions from transversalis, pectineus, psoas, and iliacus fasciae, has 3 compartments. A femoral hernia most often occurs in the most medial compartment. The femoral canal is bounded laterally by the femoral vein. The medial margin is transversus abdominis aponeurosis insertion and transversalis fascia. The femoral canal holds lymphatic channels and lymph nodes.

The superolateral border of the Hesselbach triangle is the inferior epigastric vessels. The inguinal ligament constitutes the inferolateral side. The lateral edge of the rectus sheath is the medial side.

The borders of the internal inguinal ring are the transversalis fascia circumferentially and deep, the arch of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles superomedially, and the iliopubic tract inferolaterally. The course of the spermatic cord or round ligament through the abdominal wall defines the inguinal canal. Transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia combine to make the floor of the inguinal canal in 75% of persons, while a minority have only transversalis fascia. The external oblique aponeurosis is anterior, and the inguinal ligament is inferior.

The vas deferens and the testicular artery and vein constitute the spermatic cord. The innominate fascia extends onto the cord as the external spermatic fascia. The cremasteric fascia and the cremaster muscle extend from internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis to provide the most external investment of the cord. The next layer, the internal spermatic fascia is an extension of the transversalis fascia and contains the cord structures and tunica vaginalis or an indirect hernial sac when present.

The inferior epigastric artery, which arises from the external iliac artery and courses with its companion vein vertically in the preperitoneal fat, is the anatomical point differentiating indirect inguinal hernias and direct inguinal hernias. Those presenting superolateral to the inferior epigastric vessels are indirect inguinal hernias, while those arising inferomedial to these vessels are direct inguinal hernias.

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originate principally from the first lumbar nerve root and have contributions from the 12th thoracic root. The nerves traverse the transversus abdominis muscle in the middle of the iliac crest, are deep to the internal oblique muscle until the anterior superior iliac spine, and then become superficial just beneath the external oblique aponeurosis.

The ilioinguinal nerve then runs anterior to the spermatic cord in the canal to receive sensation from the pubis and the upper scrotum (labium majus). The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, which arises from the first and second lumbar nerve roots, becomes superficial near the internal ring to supply motor fibers of the cremaster muscle and sensation for the scrotum and medial aspect of the upper thigh.

The intraperitoneal view has the medial umbilical ligament as the lateral border of the bladder, and the lateral umbilical ligament helps to identify the inferior epigastric vessels. The internal inguinal ring is the apex of a triangle formed medially by the ductus deferens and laterally by the testicular vessels. The base of the triangle contains the external iliac vessels, which may be injured during laparoscopic hernia repair. The pubic tubercle, the iliopubic tract, the transversus abdominis muscular arch, the lacunar ligament, the pectineal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle are usually easily visualized.

The obturator internus muscle arises from the margins of the obturator foramen and the obturator membrane. The muscle fascicles exit the pelvis at the lesser sciatic foramen and have a tendinous insertion on the medial surface of the greater trochanter of the femur. The obturator vessels and nerve pass through the obturator canal, which is superior in the obturator foramen.

The obturator canal runs obliquely in the medial thigh between the pectineal, external obturator, and long adductor muscles. The anterior surface of the second through fourth sacral vertebrae gives rise to the piriformis muscle to have a tendon traversing the greater sciatic foramen. Above and below this tendon, in the greater sciatic foramen, are the suprapiriform and infrapiriform foramens. The superior gluteal vessels and nerves exit through the suprapiriform foramen; the sciatic nerve, perineal nerves, and pelvic vessels pass through the infrapiriform foramen.

Contraindications

Contagious disease, diaper rash, nearby open wounds, an upper respiratory tract illness, or other intercurrent illness should delay an elective procedure. Other delays probably increase the risks of operative complications. Nonoperative observation is wise when the risk of operation exceeds that of potential problems from the hernia.

No comments:

Post a Comment